by Art Kilgour

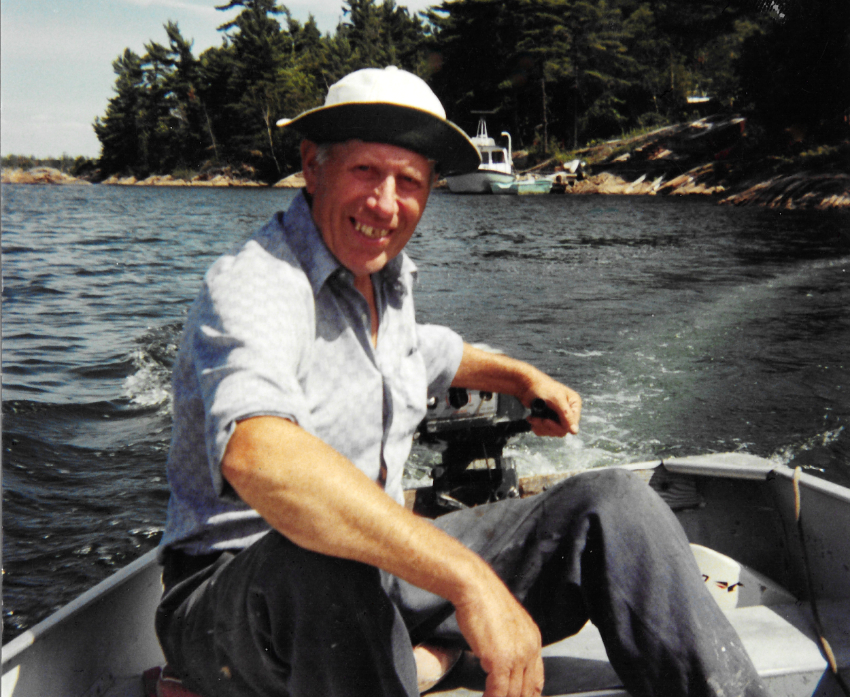

Some of the older cottages in Bayfield Inlet feature distinctive stonework in their chimneys, pathways, stairs, docks, boathouses, saunas or patios. Much of that was painstakingly laid by an Irish stonemason named John Murphy, who worked here diligently in the summers from 1950–1964, and then again in the 1980s and ’90s.

Using hand labour, basic tools and small boats, he hauled stone from Parry Sound and mixed mortar on site, working steadily for many years to put a stone “face” on the inlet we know today.

For example, his stonework adorns:

Lynne Hindmarsh remembers John Murphy, who worked for her in the 1980s: “He was a real angel, a stone angel. He was always happy, always smiling and always chatting with me.”

He came upon our area quite by chance but came to love it, even though it was far from his Irish home. Here’s his story, pieced together from a post on our Facebook page by his son (also John Murphy) as well as a conversation with him over the phone in March, plus interviews with Bayfielders who remember the elder Murphy, who is long gone.

• • • • •

John Murphy was born in County Wicklow, south of Dublin on the Irish Sea, in 1922. He trained as a stonemason in his teens, but his career got interrupted by WWII and then by travel to Spain and Mexico. He ended up in Toronto in 1950 and met Budd Feheley (pronounced “Feely”) when he worked briefly as a nighttime security guard at the older man’s downtown graphic design firm.

They were an unlikely pair: Feheley, the trained artist, successful businessman and later, a major collector of Inuit art, and Murphy, the rural Irish tradesman with a serious case of wanderlust. But after Murphy mentioned his masonry skill, Feheley made him a proposal: would he come and help build a new cottage at a property the Canadian had just bought in Bayfield Inlet? Yes, came the enthusiastic reply, and a trip north was quickly arranged.

By the time they reached Barrie, the men were already the best of friends. Feheley was charmed by Murphy’s Irish wit and warmed by their shared Catholic heritage. At the end of the four-hour trek to the cottage on rough roads, “his stomach was sore from the stories my father told him about growing up in Ireland,” says John’s son today.

• • • • •

During the first few summers, Murphy’s initial projects were all at Feheley’s cottage: stone patios by the docks, stone floors inside the house, two stone fireplaces. Several years later, he even built a flagstone tennis court on the island, when Feheley complained that his highbrow Toronto friends (the Eatons) wouldn’t come north if they couldn’t play a game of tennis in the afternoon! (Budd Feheley also served as BNIA President in 1967–68.)

Murphy said, “No problem!” He had handled dynamite in the army, and somehow got his hands on a case of explosives from a road construction crew. The two of them worked together to blast away the rock in the middle of Feheley’s island, says Murphy’s son.

“They were excited to see the dynamite moving huge boulders. And as they worked, they got braver and braver, using more dynamite. But after high fiving each other, they turned to look at the cottage and realized they had cracked all the windows,” says John. Whoops.

Budd and John spent a lot of time together, so when Feheley’s mother died suddenly at the cottage, Murphy volunteered to take her body back to the mainland by boat. “They were that close,” remembers the son. Then he adds: “She didn’t even get to finish her G&T,” displaying the same Irish wit as his father.

Murphy was almost the wealthier man’s butler, according to his son. He drove Feheley’s car, picked his kids up at school, cooked, and helped with a multi-year renovation of his stone mansion on Drumsnab Road in Rosedale.

• • • • •

So, how did Murphy’s bi-continent life work, exactly? Crucially, he was unmarried until almost the age of 50. For his first two decades with Feheley, he’d work in Bayfield Inlet from April to September—first for John, and then increasingly for other cottagers. He’d stay in Toronto or go back to Ireland in the winter, except for two years in 1962–63 when he over-wintered at Feheley’s cottage. Dennis Scale remembers Murphy as a “sheep farmer” in Ireland, but that was only a brief phase of his life, while he also renovated a stone castle!

In the mid-1960s, Murphy worked during the summers on Imperial Oil’s lake boats (there’s the wanderlust again). That’s how he eventually met his wife Carmel in Sarnia, whom he married and eventually had three sons with. John is the eldest, born in 1970, when his father was 48. The family moved back and forth between Sarnia and Ireland in the years that followed but, by the 1980s, John started returning to Bayfield Inlet and doing stonework again, at Budd Feheley’s urging.

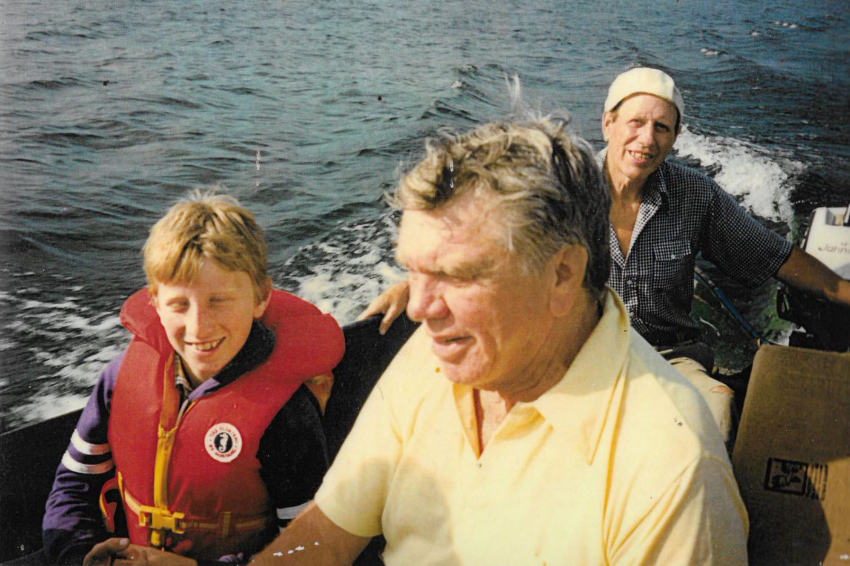

“My mother wasn’t crazy about Bayfield,” says John, “and she’d only stay for a month each summer.” But his father loved the outdoors and the hard work. He’d bring his eldest son with him, taking him abruptly out of school each April and fly to Toronto, with airplane tickets paid by Budd Feheley. The elder Murphy was in his 60s by then and needed his son’s young muscle for his stonework.

• • • • •

Lynne and Harry Hindmarsh, who cottaged further west along the main channel from Feheley, hired Murphy in the 1980s to improve their Bayfield Inlet property. Lynne was an avid collector of stones —Georgian Bay gneiss from Painted Rocks and elsewhere. She provided Murphy with local material for their island projects.

“John was a gem,” says Hindmarsh now. “He was a real angel, a stone angel. He was always happy, always smiling and always chatting with me.” She also says he was a fantastic worker, “a real steady Eddy.” He’d bring a sandwich lunch and work all day long, except when he was talking to Lynne. (Harry Hindmarsh died in 1990, but Lynne still cottages at the same property today, in her 80s.)

• • • • •

John says that his dad’s last working trip to Bayfield Inlet was in 1995. He was getting too old for the hard labour of masonry. He and Budd Feheley remained friends for the rest of their lives. Feheley visited Murphy in Ireland in the 1990s and they continued to talk frequently by phone, even from their respective nursing homes very late in life. Budd Feheley died in 2009 in Toronto. He was 92. John Murphy died in Ireland, two years later. He was 89.

It’s clear that Bayfield Inlet captured the hearts of both John Murphys. “My dad had an amazing life, part of it in the wilds of Canada, which I also got to know as a teenager,” says the son.

He also tells me, “You’re so lucky to have a little place in Bayfield Inlet, with all that’s going wrong in the world today. The minute you get up there, you’re a totally different person, and the rest of your life just melts away.”