by Art Kilgour

On an otherwise unremarkable July afternoon in 2021 I noticed a strange cloud approaching our cottage in Bayfield Inlet from the north. It was novel to me, a long tube, easily stretching 10 kilometres out into the open bay. The weather was otherwise calm, with puffy, separate cumulous clouds above. The outlier cloud was moving quickly southward, and it appeared to be rolling sideways, with a mind of its own.

Was it a nascent tornado, about to turn vertical and get violent? I took the photo above and dashed inside. It passed quietly by within a few minutes.

When I posted to the BNIA Facebook group others had noticed the cloud too. Andrew Kolody of Nares Inlet was in his boat when he felt an abrupt temperature drop of 5–10 degrees, “as if we’d just passed an iceberg.” Then he saw the cloud pass overhead. “Perhaps it’s an alien scan of the earth,” joked Timothy Ord.

Identification was easy once I typed “rolling cloud” into Google. A roll cloud is a rare event, especially in an otherwise calm sky. Its isolation in the sky makes it photogenic—just search #rollcloud in Instagram.

I recently quizzed Scott Sommerville about my find. He’s a lifelong Environment Canada employee who cottages in Pointe au Baril. After looking at my photo he commented, “Oh yeah, that’s what we call a fair-weather roll cloud.”

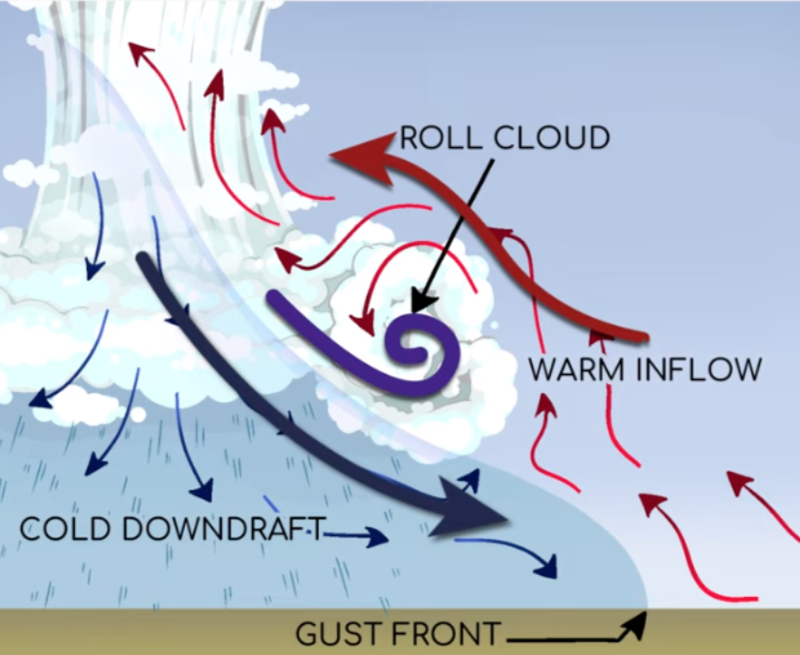

I asked what causes them. “It’s a combination of temperature and pressure differences in the sky, usually along a coastline,” he explained. “There’s a strong downdraft of cold air at the leading edge of the cloud that you can’t see, which causes the rolling motion.” That accounts for the abrupt cooling that Andrew Kolody noticed.

More commonly, however, roll clouds form at the leading edge of a thunderstorm. Look at the example below from Pointe au Baril later in the summer of 2021, just before a particularly violent storm. Pointe au Baril cottager Libby Hunter took the photo below looking north towards Champlain Monument Island, opposite the Ojibway Club.

“Oh yeah, that’s really dramatic!” enthused Sommerville about Hunter’s photo. “You can see the roll cloud just ahead of the storm, then the wall clouds stacked up behind—sometimes called shelf clouds—and finally, intense rain in the black clouds behind them.”

Sarah McCoy, another Pointe au Baril cottager, wrote, “The wall clouds floated past like silent, dark ships. Nothing seemed to happen. The atmosphere at our island felt too quiet … ”

The same August 2021 storm spawned another unusual event. The thunderstorm’s low pressure caused the lake to rise 12 inches in short order, and then subside again just as quickly (all within a day). That’s called a seiche (pronounced SAYsh) tide.

“Have you ever noticed how calm it gets before a thunderstorm?” Sommerville asks. “That’s because the sudden low pressure of the storm front means the air is rising quickly. There’s no wind, so you can’t feel it, but falling pressure at the surface reduces the weight of air over the lake, and the water rises,”like a hurricane’s storm surge on coastal shores.

We’re accustomed to having our water levels rise and fall in Bayfield-Nares, sometimes quickly. Strong westerly winds create waves out in the open, which push water into our archipelago, raising levels at the shoreline. The opposite happens when wind blows from the north or the east. These small, weather-related fluctuations are unrelated to year-over-year changes in water levels.

A seiche tide is bigger and rarer than that, and more abrupt. If a thunderstorm like the one described above brings strong west winds and low pressure, then the combination can cause a rapid change in water levels and produce currents in narrow channels.

Dennis Scale, the retired jack-of-all-trades of Springhaven Services, says, “We’d notice that the water on our beach would suddenly advance 4–5 feet, then retreat again.” Evidence of a seiche. “That meant that the water had risen 4–5 inches. And if I was driving my boat through the little S-bend in Nares, I would feel the current.”

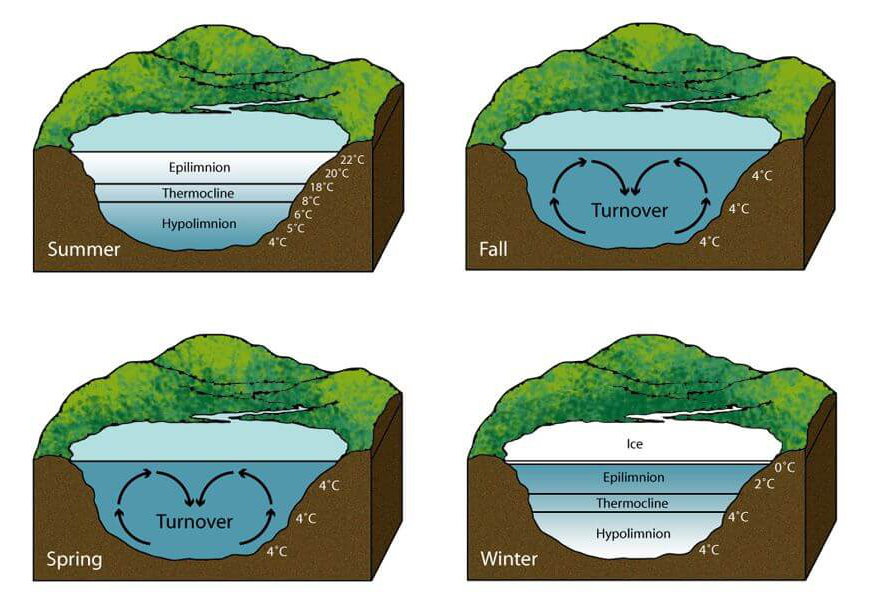

Have you ever jumped off your dock in late August and felt a shock of suddenly cold water, a big change from the day before? That’s because of temperature stratification in the summer. Warm water is less dense than cooler water, so it accumulates at the surface.

That can be disrupted by an easterly wind, which causes the water to mix with cooler water below the surface, but things return to normal if the sun shines and nighttime temperatures are well above zero. Even in September, you can enjoy swims at 65°F or 18°C. That’s not warm, but much deeper in the lake the water is 4°C even in mid-summer.

The cooler daytime temperatures of October (and eventually, freezing nighttime temps) bring an end to our stratified lake. And at a certain point, the lake “turns over”, with temperatures equalizing from top to bottom. You’re probably not swimming at this time of year anyway, but the drop would still be dramatic over a few days or even within a few hours.

This annual cycle, with turnovers in the fall and spring, and equilibria in the winter and summer (see chart), mixes nutrients and oxygen through our lakes in a complex process. According to the Clean Lakes Alliance, “It’s like the lake taking a deep breath … a fresh start every fall and spring.” (Read more about lake turnover here.)

“Georgian Bay is so big that it creates its own weather,” says Scott Sommerville, and the evidence is these peculiar things that we may notice at the cottage, where we live so much closer to the outdoors.